Everything about CSP

Imagine CSP as a security guard for a website. Its job is to keep an eye on who and what is allowed to come into a website, just like a bouncer at a club who checks IDs to make sure only the right people get in.

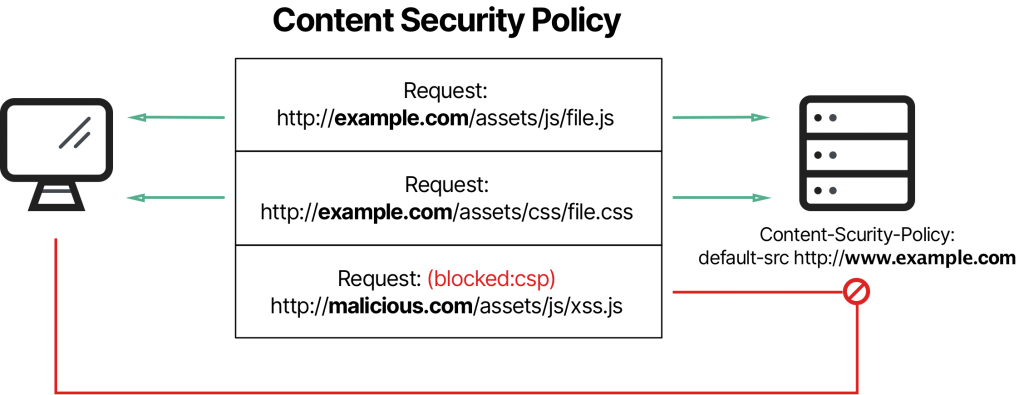

Content Security Policy (CSP) is a security feature implemented on the server side, but it is enforced by web browsers. In other words, CSP is both a server-side configuration and a browser-enforced security measure.

Here's how it works:

- Server-Side Configuration: Website owners or administrators configure CSP on the server where the website is hosted. They set the rules and policies that define which sources of content (such as scripts, images, styles, and fonts) are considered safe and allowed to be loaded or executed by web pages served from their domain.

- Browser Enforcement: When a user visits a website, the server sends the CSP policy as an HTTP response header. The user's web browser then interprets and enforces this policy while rendering the web page. The browser restricts the loading and execution of content based on the rules defined in the CSP policy.

- CSP rules are called "directives," and they determine where content can come from.

- Some common directives include:

script-src: Determines where JavaScript code can come from.img-src: Decides where images can be loaded from.style-src: Specifies where stylesheets can be loaded.default-src: Sets the default rules when specific rules are not provided.

- Each directive has its own purpose and controls a specific type of content.

Sources: Where Content Comes From

- The directives use "sources" to define where the content can come from.

- Common sources include:

*: Means content can come from anywhere (not recommended for security).self: Refers to the website itself.example.com: Specifies a specific website as an allowed source.data:: Allows content to come from data in the web page.blob:: Allows content from local browser storage.

- Each source is like a set of instructions for CSP to follow.

Examples of CSP Rules and Sources

- If a website wants to allow scripts only from itself and a trusted domain, it might have a CSP directive like this:

script-src 'self' trusted-domain.com;

- If it wants to allow all content except data: and blob:, it might use:

default-src *;

- If it needs to allow inline scripts, it might use:

script-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline';

- If it wants to prevent the use of

eval()in JavaScript, it can use:script-src 'self' 'unsafe-eval';

Now, if this security guard, CSP in our case, isn't doing a good job, it can lead to trouble. Here's how:

1. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks: Without CSP or with a weak CSP, hackers can sneak harmful code into a website. It's like allowing a thief to get inside the club and steal things.

But does CSP eliminate XSS? No, sanitization is still required to ensure overall security. It is more like an additional layer to make it harder for the hackers.

2. Data Leakage: If CSP isn't set up correctly, it might accidentally let sensitive information like passwords or personal data leak out. It's similar to having a leaky faucet in your home – water (data) flows where it's not supposed to.

3. Malicious Content: A vulnerable CSP can let malicious content, like harmful scripts or ads, show up on a website. It's like allowing a stranger to put up posters inside your house, you wouldn't want that.

4. Clickjacking: If CSP is not properly configured, attackers can trick users into clicking on something they didn't mean to. It's like someone putting a fake cover on a book to make it look exciting, but inside, it's not what you expected.

In simple terms, a weak or vulnerable CSP is like having a lazy security guard who doesn't check IDs properly, doesn't stop troublemakers from entering, and lets bad things happen inside. To avoid this, websites need to set up CSP properly to protect themselves and their visitors from these online dangers.

Challenges For CSP

Let's discuss the challenges of using Content Security Policy (CSP):

- Browser Compatibility: Not all web browsers fully support CSP, especially older ones. This means that CSP may work differently or not at all in some browsers. Web developers need to account for these differences.

- Setting Up CSP is Complex: Configuring and implementing CSP can be quite complex, especially for websites with lots of different parts. Getting the right balance between security and functionality is a challenge.

- Dealing with Existing Code: If a website is already up and running, adding CSP can be tricky. Older code may not follow CSP rules, and adapting it can be time-consuming.

- Blocking Legitimate Stuff: Sometimes, CSP can block things that are actually safe, like images or scripts needed for a website to work correctly. Striking the right balance is tough.

- Reporting and Debugging: When CSP blocks something, it sends reports. These reports can be overwhelming and tough to make sense of. Fixing issues can also be a complex debugging process.

- Third-Party Dependencies: Modern websites often rely on stuff from other places (like social media widgets). These external things might not play nicely with CSP, so integrating them safely can be a puzzle.

- Mixed Content: CSP enforces strict rules about how websites load content over secure connections (HTTPS). If a website has a mix of secure and insecure content, CSP can block the insecure parts. Fixing this can be challenging.

- Security Mistakes: If CSP is set up incorrectly, it can introduce security holes instead of fixing them. Making sure nonces (security keys) are generated well and CSP headers are set right is crucial.

- Browser Extensions: Some browser extensions can inject code into web pages, and they can ignore CSP rules. Dealing with this situation is complicated.

- Dynamic Web Apps: Websites that change a lot or use advanced technology can be challenging to secure with CSP because they may need complex CSP rules.

- Ongoing Maintenance: CSP isn't a one-time setup, it needs regular checks and updates to stay effective against new threats or changes in your website.

CSP Examples

Let's explore some examples of how Content Security Policy (CSP) works and how it can mitigate attacks. We'll focus on Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks, one of the primary threats CSP aims to prevent.

Example 1: No CSP

Without CSP, a web page is vulnerable to XSS attacks. Imagine a vulnerable web page with the following code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Welcome, <span id="username"></span>!</h1>

<script>

var username = getParameterByName('username');

document.getElementById('username').textContent = username;

</script>

</body>

</html>

In this example, the page takes a username parameter from the URL and displays it on the page. An attacker could craft a malicious URL like this:

https://example.com/page?username=<script>alert('XSS');</script>

Without CSP, the malicious script would execute, and the user would see an alert with 'XSS'.

Example 2: Basic CSP

Now, let's introduce a basic CSP header in the web page's response:

Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self';This CSP policy restricts content to be loaded only from the same origin (the 'self' directive). In this case, the script from the attacker's domain won't be loaded, preventing the XSS attack. The browser will block it, and the user sees no alert.

Example 3: Allowlist CSP

In a more complex scenario, a CSP policy may allow specific domains for scripts. For example:

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' trusted-scripts.com;With this policy, only scripts from the same origin ('self') and 'trusted-scripts.com' are allowed. If an attacker tries to load a script from their domain, it's blocked by the browser.

For example, this will get blocked since this domain is not in the trusted list.

<script src="https://attacker.com/malicious.js"></script>Example 4: Inline Script

CSP can also prevent inline scripts (scripts directly in the HTML code) with 'unsafe-inline':

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline';However, a clever attacker might try to bypass this by injecting code directly into the HTML. In this case, CSP would still block it:

<script>alert('This is blocked by CSP');</script>Bypassing CSP Examples

Here are examples of how Content Security Policy (CSP) can be bypassed in different scenarios:

Example 1: Data URI Bypass

Let's say a website's CSP allows 'data:' URIs for scripts:

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' data:;

An attacker can bypass this by encoding their malicious script as a data URI and injecting it directly into the HTML code:

<script src="data:text/javascript;base64,PHNjcmlwdD5hbGVydCgnWE1MIEF0dGFjayk7PC9zY3JpcHQ+"> </script>

In this case, the attacker has encoded the JavaScript code as a base64 data URI and embedded it directly into the 'src' attribute of the script tag, bypassing CSP.

Example 2: DOM-Based Bypass

CSP might restrict the use of inline scripts with 'unsafe-inline':

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline';

However, an attacker might find a way to execute code without using inline scripts, for example, by manipulating the DOM:

<div id="mydiv"></div>

<script>

var code = 'alert("Bypassing CSP with DOM manipulation");';

var script = document.createElement('script');

script.text = code;

document.getElementById('mydiv').appendChild(script);

</script>

In this case, the attacker dynamically creates a script element and appends it to the DOM, effectively executing the code without using an inline script.

Example 3: Whitelist Bypass

Suppose CSP allows scripts from 'example.com':

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' example.com;An attacker might discover a subdomain or a subpath that's not explicitly covered by the CSP policy:

<script src="https://sub.example.com/malicious.js"></script>If the CSP policy only specifies 'example.com', the attacker's script from 'sub.example.com' could still execute because it's not explicitly blocked.

Example Vulnerabilities:

Issue: Vulnerable CSP Configuration

CSP is supposed to decide who and what can enter your fortress (website) to keep it safe.

- If you tell your security guard (CSP) that a certain public content delivery network (CDN) is allowed inside by its name, that's like saying, "Hey, let these guys from that CDN come in!"

- Now, the problem is, if that CDN has any weak points or risky stuff, your security guard doesn't know about it. So, anything from that CDN, even the risky stuff, is allowed in.

- To make matters worse, if you also tell your security guard (CSP) that it's okay to use "unsafe-eval" or "unsafe-inline" sources, you're basically saying, "Feel free to do anything, even if it's risky!"

Imagine you have a snippet like this:

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src 'unsafe-eval' https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com;">

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/angular.js/1.0.8/angular.min.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div ng-app ng-csp>{{$on.constructor('alert(1)')()}}</div>

</body>

In this case:

- The CSP policy (

script-src 'unsafe-eval' https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com;) allows scripts to be loaded from the specified CDN (cdnjs.cloudflare.com) and permits the use ofunsafe-eval. - You're using AngularJS from the CDN.

- Within the page, there's an AngularJS expression

{{$on.constructor('alert(1)')()}}. This is a sneaky way to use AngularJS to execute the JavaScript codealert(1).

With this configuration, a malicious actor could potentially inject harmful JavaScript code using AngularJS because unsafe-eval is allowed by CSP. This is a security risk because it opens the door for code execution that might not have been intended.

In technical terms, it's like saying, "I trust this CDN, and I'm okay with allowing potentially dangerous code execution methods." To enhance security, it's essential to carefully craft your CSP policies to only allow trusted sources and to avoid overly permissive settings like unsafe-eval and unsafe-inline.

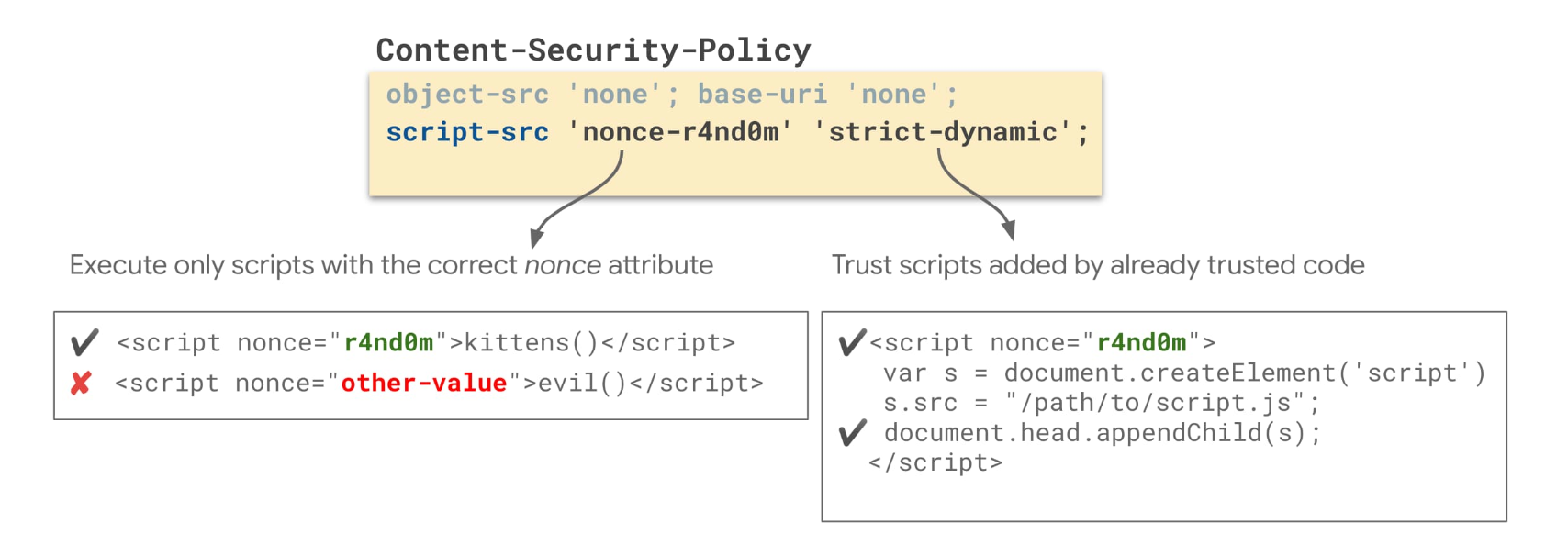

Issue: Nonce Reuse

In CSP, a nonce is a cryptographic value that is used to allow specific inline scripts to run. Nonces are generated by the server and are included in the CSP header. They serve as a security token, ensuring that only scripts with the correct nonce value are executed. However, if nonce values are not managed securely, it can lead to a vulnerability:

Nonce Security Importance:

- The strength of CSP relies significantly on the uniqueness and unpredictability of nonce values.

- Nonces are used to prevent the execution of unauthorized inline scripts, making them a crucial part of CSP's security model.

Static or Weak Nonces:

- If nonces are static (i.e., they never change) or are generated using a weak algorithm, attackers can potentially guess or obtain the nonce value.

- If an attacker can predict or guess the nonce, they can craft malicious scripts with the correct nonce value, effectively bypassing the CSP policy's protection.

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'nonce-static-nonce';In this example, the CSP policy uses a static nonce value 'static-nonce.' If an attacker discovers or guesses this value, they can create an inline script that matches this nonce, and it will be executed, bypassing the CSP policy.

To Read About Similar Vulnerabilities Visit - https://0xn3va.gitbook.io/cheat-sheets/web-application/content-security-policy#allowed-data-scheme

CSP Implementation Case Study Of Linkedin

LinkedIn has always been dedicated to providing a safe and secure platform for its members, and a crucial part of achieving this is through robust application security measures. Let's look at LinkedIn's remarkable journey in implementing and refining its Content Security Policy (CSP) – a critical component in fortifying web application security.

The Challenge

LinkedIn was like a thriving neighborhood that was getting bigger by the day. To keep everything safe and sound, they had a set of rules called Content Security Policy (CSP). It was a bit like locking your doors to keep your home secure. But here's the twist: as LinkedIn got busier and bigger, managing these rules became like having a giant pile of keys to sort through. Every change had to be reviewed and approved manually. Not fun, right?

For developers, it was like trying to redecorate a room blindfolded – not knowing if your changes would work until it was too late.

The Solution

LinkedIn decided to flip the script. They wanted to make things smoother and more efficient. Their five big goals were:

- Keep Changes Small: They wanted to make sure any changes they made wouldn't mess up the whole neighborhood – just a part of it.

- Empower Developers: Instead of LinkedIn being the security police, they wanted developers to call some shots and make changes themselves.

- Make Testing Easy: No more blindfolded decorating! Developers should be able to test their changes without any roadblocks.

- Level Up Security: The idea was to make things safer without slowing things down.

- A Swiss Army Knife Solution: LinkedIn didn't want to just fix CSP. They wanted a tool that could do more.

Decentralized CSP System

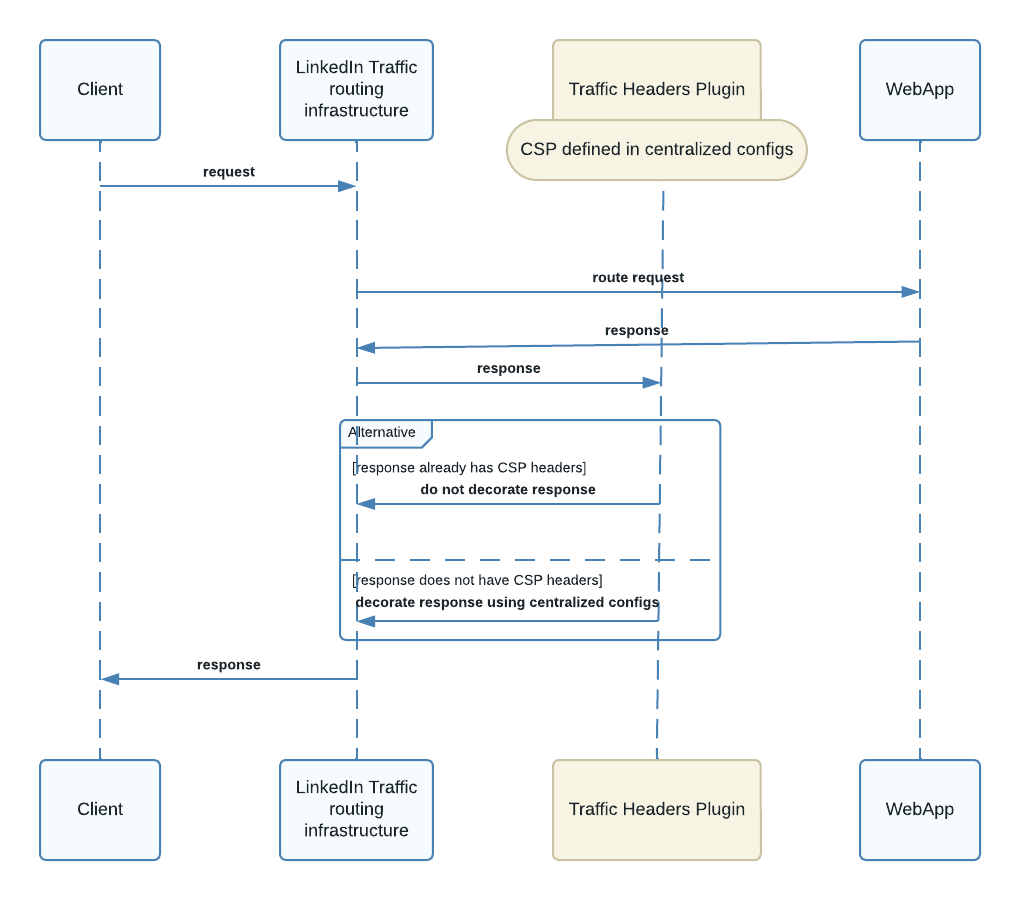

To put their plan into action, LinkedIn introduced something called a CSP Filter. Think of it as a lifeguard at the online beach, keeping an eye on everyone's safety. This Filter lives in their system's front end.

Here's how it works: Developers can now set security settings as part of their app's setup. When someone uses LinkedIn, and the system sends a response, the CSP Filter steps in. If the developer set security rules, the Filter adds the right settings to the response. If not, it just lets things be.

After that, when the response heads back to your device, there's a Traffic Headers Plugin that checks if there are security settings. If they're missing, the plugin adds them. This way, they make sure every response is locked up tight.

The Good Stuff and the Hiccups

The new system brought lots of good things. Changes were less of a hassle, developers had more control, and testing was a breeze. But, as with anything new, there were challenges. They needed to keep an eye on things and make sure everyone was playing by the rules.

To solve these issues, LinkedIn took a "shift-left" approach. They added security checks when developers put in their code. They also set up rules to make sure only safe security settings were used. If someone tried something risky, they'd get a virtual red flag – their changes wouldn't go through until they fixed it.

So How Does This Decentralization Work?

LinkedIn's CSP implementation, decentralization refers to the shift away from a single, centralized system for managing Content Security Policies (CSP) to a more distributed and developer-centric approach. Here's how it works:

Centralized Model (Before):

- In the old, centralized model, there was a single location or a central authority responsible for defining and managing CSP rules.

- These rules were maintained and enforced by a central team (in this case, LinkedIn's Application Security team).

- Any changes or updates to CSP rules had to go through this central team for review and approval.

- The rules were applied globally, affecting all parts of the application uniformly.

Decentralized Model (After):

- In the new decentralized model, LinkedIn moved away from having one central authority for CSP rules.

- Instead, developers working on various parts of the platform can define and manage their own CSP rules within their application configurations.

- When a request is processed, the response is checked by a CSP Filter, which is a part of the frontend frameworks. If developers have defined CSPs for their specific applications, the CSP Filter applies these rules to their responses.

- If developers haven't set CSPs, the CSP Filter doesn't intervene, allowing them to work without CSP restrictions.

- The Traffic Headers Plugin, another component, steps in later to ensure that every response includes a CSP header.

In summary, the decentralization comes from giving individual application developers more control over the CSP rules for their specific parts of the platform. It reduces the need for a central team to manage and approve all CSP changes, empowers developers to make these changes themselves, and allows for greater flexibility and customization in applying CSP rules across different areas of LinkedIn's services.