Strict Transport Security (HSTS), X-Frame-Options and Referrer-Policy

In my previous blog, we explored Content Security Policy (CSP), a vital security header designed to prevent web security attacks. Now, let's dive into some other essential security headers that you should be aware of to increase the security of your web applications.

- Strict Transport Security (HSTS)

- X-Frame-Options

- Referrer-Policy

Now, let's delve into each header in more detail:

Strict Transport Security (HSTS)

HSTS tells the browser to always use HTTPS to communicate with the website while ensuring secure connections and mitigating SSL/TLS-stripping attacks.

HSTS is like a guarantee for secure communication. By setting the Strict-Transport-Security header, we request the web browsers to always connect via HTTPS, regardless of whether the user enters an HTTP URL. This simple but powerful directive ensures that your user's data is encrypted, guarding against potential SSL/TLS-stripping attacks.

SSL stripping is a sophisticated man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack aimed at downgrading a user's secure HTTPS connection to an insecure HTTP connection, leaving their sensitive data exposed. Attackers use various techniques to intercept and manipulate traffic between a user and a website.

Initial Connection: When a user attempts to connect to a website over HTTPS, their browser sends a secure request.

GET https://example.com/login HTTP/1.1

Attacker's Interception: The attacker intercepts this request and sends an initial response to the user, which appears to be from the intended website. However, the attacker responds with an HTTP version of the page instead of HTTPS

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 186

<html>... (insecure content) ...</html>

- Browser's Reaction: Since the initial response is not over HTTPS, the user's browser may accept it, thinking it's okay to proceed without encryption.

- Attacker's Relay: Simultaneously, the attacker establishes a secure connection to the intended website in the background using HTTPS.

- Secure Data Extraction: Any sensitive information, such as login credentials, submitted by the user is captured by the attacker while it passes through the insecure connection.

HSTS is a defense mechanism against SSL stripping attacks. It ensures that a website is accessed only over secure HTTPS connections, even if the user initially requests HTTP. Here's how it works:

- HSTS Header: When a website enables HSTS, it sends an HTTP response header to the user's browser, indicating the HSTS policy, like this:lua

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preloadmax-age: Specifies the duration for which the HSTS policy should be enforced.includeSubDomains: Extends HSTS protection to all subdomains.preload: Submits the website to the HSTS preload list maintained by browsers.- Browser's Behavior: Upon receiving the HSTS header, the user's browser remembers to always connect to the website via HTTPS for the specified duration. It also applies this policy to all subdomains.

- Prevention: With HSTS in place, even if an attacker attempts an SSL stripping attack by downgrading the connection to HTTP, the user's browser will automatically upgrade it back to HTTPS. The attacker cannot intercept or manipulate the traffic because the browser insists on a secure connection.

SSL stripping in action (1000 USD Reward)

Five years ago, I discovered a significant security vulnerability in an Android application (HackerOne Private Program). This vulnerability allowed the application's credentials to be exposed in clear text over the network, despite the data supposedly being transmitted securely over port 443 (HTTPS). To exploit this vulnerability and capture sensitive information, I used a tool called Ettercap and the SSL stripping plugin along with ARP spoofing. This approach allowed me to intercept and capture the plaintext credentials as they were transmitted over the network, highlighting a critical security flaw in the application's encryption and data protection mechanisms.

Directives:

Remember that once HSTS is enabled, it can be challenging to revert to HTTP. Be cautious and thoroughly test your HTTPS configuration before deploying HSTS headers to avoid potential issues.

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=<seconds>

This directive is the core of HSTS and specifies the maximum duration, in seconds, that the browser should enforce HTTPS for a website. For example, if you set max-age to 31536000 (1 year), the browser will enforce HTTPS for your site for one year from the first visit. This directive is mandatory in HSTS policy.

-----------------------------------------------------

Strict-Transport-Security: includeSubDomains

When this directive is included in the HSTS policy, it extends the policy to all subdomains of the website. This ensures that all subdomains are also accessed via HTTPS, enhancing security across the entire domain.

-----------------------------------------------------

Strict-Transport-Security: preload

By adding the "preload" directive, you submit your website to the HSTS preload list maintained by major browsers. Once accepted, your website will always be accessed via HTTPS, even on the user's first visit, without relying on the initial HSTS header from your server. This is a proactive measure to ensure secure connections.

-----------------------------------------------------

Strict-Transport-Security: includeSubDomains; preload

This combination includes both the "includeSubDomains" and "preload" directives. It enforces HSTS for all subdomains and includes the website in the HSTS preload list.

Vulnerability:

Without HSTS, your website may be accessed over an unencrypted HTTP connection, which poses a significant security risk. A hacker can exploit this vulnerability to intercept unencrypted communication between a user's browser and your website, potentially exposing sensitive data.

The Exploitation:

Now, let's say a hacker wants to take advantage of this gap:

- User Trickery: The hacker tricks a user into visiting a fake version of your website. They might send a phishing email or create a misleading link that appears to lead to your site.

- Unsecured Connection: The tricky part is that this fake website operates over HTTP, not secure HTTPS. Since the user doesn't have HSTS protection enabled, their browser won't automatically redirect them to the secure version of your site (HTTPS).

- Data Theft: Because the connection isn't secure, any information the user sends to this fake website can be intercepted by the hacker. This could include login details, personal info, or anything else they enter on the fake site.

The Remediation:

To protect your users from this kind of attack and secure your website, here's what you can do:

- Enable HSTS: Imagine HSTS as your security upgrade. You need to activate it by adding a specific instruction to your web server.

- Set the time frame: You decide how long this security upgrade lasts. In the example,

max-age=31536000means it'll be active for a year. During this time, your users' browsers will always use the secure HTTPS version of your site. - Secure Subdomains (Optional): If you have other sections or services on subdomains (like blog.yourwebsite.com), you can include them in this protection by adding

includeSubDomains. It's like extending your security umbrella to cover all areas. - Preloading for Immediate Protection (Optional): Imagine getting immediate protection even for first time visitors. You can do this by using the

preloadfeature. It adds your site to a special list, so browsers automatically load it securely, even on the first visit.

Here's what the full instruction might look like:

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload

X-Frame-Options

X-Frame-Options is like setting boundaries for who can display your website within an iframe. It guards against clickjacking attacks where malicious sites frame your content and deceive users.

Directives:

Here are explanations for the X-Frame-Options directives, which control whether a web page can be displayed in an iframe on another website:

X-Frame-Options: DENY

This directive prevents the web page from being displayed in an iframe on any other website. It offers the highest level of protection against clickjacking attacks by completely denying framing.

----------------------------------------------

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

With this directive, the web page can be displayed in an iframe, but only if the iframe's source is from the same origin as the web page itself. It helps prevent clickjacking attacks while allowing legitimate uses within the same site.

----------------------------------------------

X-Frame-Options: ALLOW-FROM uri

This directive allows the web page to be displayed in an iframe, but only if the iframe's source matches the specified URI (Uniform Resource Identifier). You can specify a specific domain or page where framing is allowed. However, note that this directive is becoming deprecated in favor of the Content Security Policy (CSP) frame-ancestors directive.

Vulnerability:

Without X-Frame-Options, your site can be framed by malicious websites, potentially leading to phishing or other attacks.

The Exploitation: Here's how attackers might exploit this vulnerability:

- User Interaction: Attackers create a fake login page for your site within an iframe on their malicious site.

- Deceptive Framing: Users unknowingly enter their login information, thinking they're on your site.

- Data Theft or Manipulation: Attackers can steal user credentials or perform actions on your site as if they were the users.

The Remediation: To protect your users from this kind of attack:

- Enable X-Frame-Options by adding the header to your server's responses.

- Use

DENYto block framing entirely, ensuring your site cannot be displayed within an iframe on any other domain.

Case Study:

For the sake of this article let's dig into this HackerOne report although this report is quite old but still gives us a decent picture of how clickjacking can be exploited, So, there's this feature on Twitter called the Player Card that lets websites embed custom videos and players in tweets. Sounds cool, right? Well, it turns out it had a security issue, a big one! The problem was that bad actors could potentially trick users into clicking on something they shouldn't.

Twitter Player Card Feature:

The Twitter Player Card is a feature that allows websites to embed customized video players or interactive content within tweets. It's a great way to enhance the tweet's engagement by providing rich media experiences directly within a user's Twitter feed. Imagine seeing a tweet that not only contains text but also includes an embedded video, audio, or interactive content like games or surveys. It's an effective way for brands, content creators, and users to share engaging multimedia content.

Security Measures in Place:

Now, let's talk about the things that led to the vulnerability in Twitter's Player Card:

- X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN: This security measure restricted the embedding of Player Card content to the same origin as twitter.com. However, it had a limitation – it only checked if the embedded content was from a different Twitter page but didn't prevent embedding from other websites. This gap allowed attackers to trick users.

- Content-Security-Policy (CSP): frame-ancestors 'self': While this feature was intended to limit where the Player Card could be displayed, it didn't behave consistently across all web browsers. Some browsers, like Safari and Internet Explorer, didn't fully support it, making the protection uneven.

- JavaScript Frame-Buster: Twitter had a JavaScript-based frame-buster in some pages to prevent clickjacking. However, this frame-buster wasn't consistently implemented across the platform, leaving some pages vulnerable to attacks.

Twitter's Update and Mitigation:

In response to the reported vulnerability, Twitter took action to improve the security of the Player Card feature. They made the following changes:

- Player Card now requires a click to open: This change ensures that users must actively interact with the Player Card to open it. This reduces the risk of unintentional clicks and mitigates the clickjacking vulnerability by requiring deliberate action from the user.

- Iframe sandbox by default: Using the "iframe sandbox" attribute by default is a security enhancement. It allows for more control over the behavior of the embedded content, making it harder for attackers to exploit vulnerabilities.

Referrer-Policy

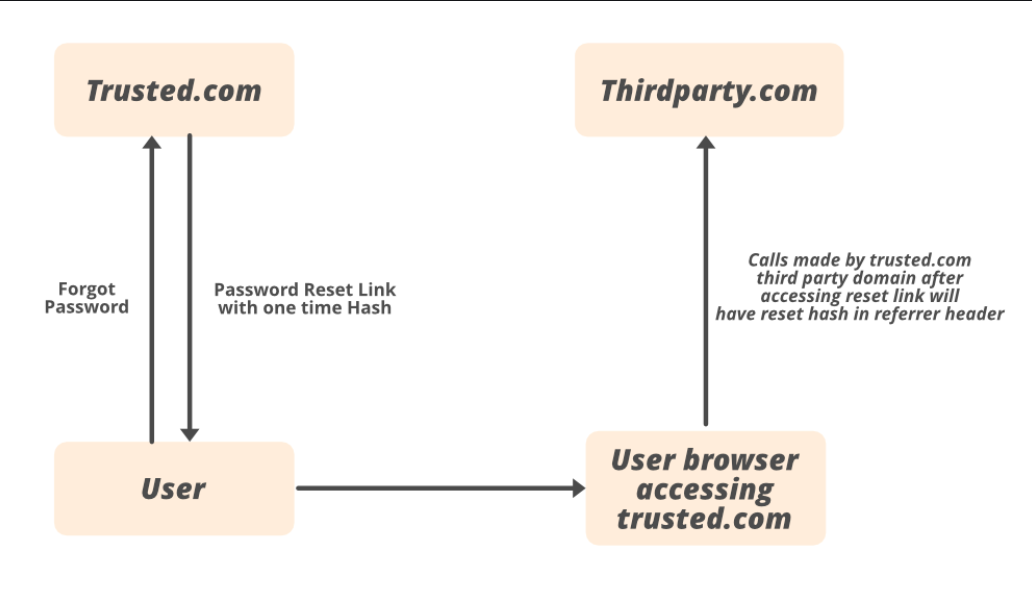

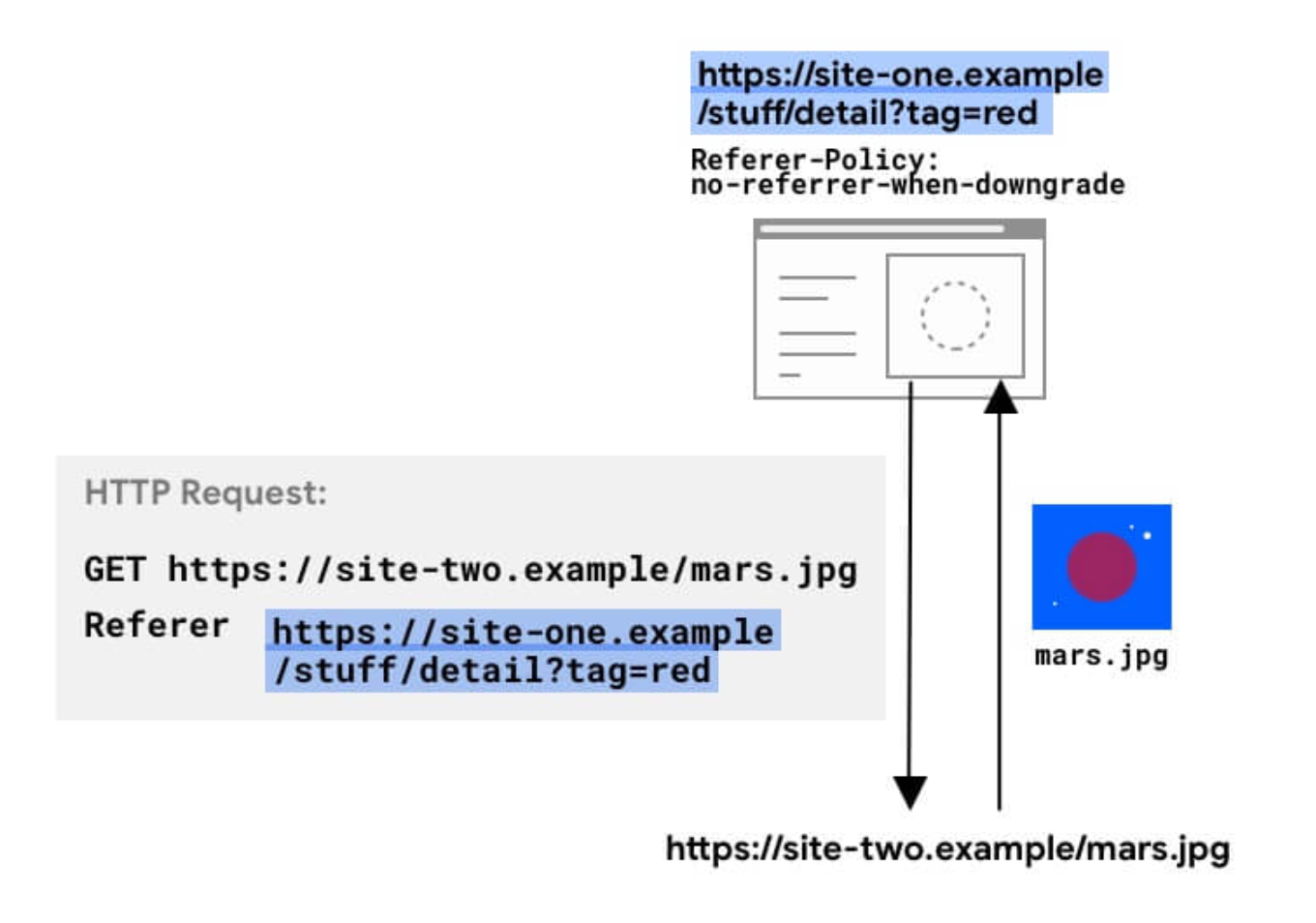

When you browse the web, your web browser often sends information about where you came from when making requests to websites. This is done through something called the "Referer" header. It tells the website you're visiting where you were before. For example, if you clicked on a link from one page to another, the Referer header would tell the second page where you came from.

The Referrer-Policy header, on the other hand, determines what kind of information is shared in the Referer header. It helps control the privacy and security of this information.

Directives:

Let's explain each of these Referrer-Policy directives, which control how much information is included in the Referer header when a user navigates from one web page to another:

Referrer-Policy: no-referrer

This policy sends no Referer information in the header when navigating to another page. It provides the highest level of privacy but may break some functionality that relies on Referer data.

--------------------------------------------------

Referrer-Policy: no-referrer-when-downgrade

This policy sends no Referer information when navigating from a secure (HTTPS) origin to a less secure (HTTP) origin. However, it sends the full Referer when both the source and destination are secure. This policy helps maintain privacy while still enabling full Referer information within secure contexts.

--------------------------------------------------

Referrer-Policy: origin

This policy sends only the origin (domain) of the referring page in the Referer header. It does not include the path or query string. This is a balance between privacy and functionality.

--------------------------------------------------

Referrer-Policy: origin-when-cross-origin

When navigating from one origin to another, this policy sends the full URL (including origin, path, and query string). Within the same origin, it sends only the origin. It balances privacy with the ability to share Referer information with external domains.

--------------------------------------------------

Referrer-Policy: same-origin

This policy sends the full Referer (including origin, path, and query string) when navigating within the same origin. However, it sends no Referer information when navigating to a different origin. It helps maintain privacy while allowing Referer information sharing within the same website.

--------------------------------------------------

Referrer-Policy: strict-origin

When navigating within the same origin, this policy sends the full Referer (including origin, path, and query string). But when going to a different origin, it sends only the origin. It provides some privacy while allowing Referer sharing within the same website.

--------------------------------------------------

Referrer-Policy: strict-origin-when-cross-origin

This policy sends the full URL (including origin, path, and query string) when navigating from one origin to another, but within the same origin, it sends only the origin. It maintains privacy while allowing Referer sharing when necessary across origins.

--------------------------------------------------

Referrer-Policy: unsafe-url

This policy sends the full Referer (including origin, path, and query string) regardless of the destination's security. It's the least privacy-conscious option and should be used sparingly, as it can expose sensitive data.

Why Does the Referer Header Matter?

The Referer header is present in different types of web requests:

- Navigation Requests: When you click on links and go from one webpage to another.

- Subresource Requests: When your browser fetches images, iframes, scripts, and other resources that a webpage needs to display correctly.

Sometimes, websites and services use the Referer information to analyze user behavior. For instance, an analytics service might use it to figure out that 50% of the visitors to a website came from a particular social network.

However, when the Referer header includes the complete URL, including the path and query string, it can pose privacy and security risks. Some URLs contain sensitive or private information. Sharing this information across different websites can compromise your privacy.

- Sensitive Information Leakage: Sample URL:

https://example.com/profile?user=12345Imagine a user is on a secure website with their profile page open. If they click on a link to an external website without a proper referrer policy, the external website might receive the complete URL, including sensitive information like the user's ID (user=12345). This could potentially compromise the user's privacy. - Cross-Origin Request Data Leak: Sample URL:

https://example.com/sensitive-dataLet's say a website contains a page with sensitive data, and it includes resources like images or scripts from external domains. Without a proper referrer policy, these external domains may receive the complete URL of the sensitive page, even if the user navigated there from a secure login page. This can expose confidential information. - Tracking Users Across Websites: Sample URL:

https://advertiser.com/tracker?user=98765Some advertising networks and trackers use Referer information to track users across websites. If a user clicks on a link to an advertiser's site from a different site, the advertiser can receive the complete URL. This allows them to track the user's browsing habits and potentially build a detailed profile. - Session Hijacking: Sample URL:

https://example.com/account/settingsIf a user is logged into their account on a website and they click on a link to another website without proper referrer policies, the second website could potentially see the user's session information, such as session tokens or authentication data. This creates a risk of session hijacking.

Control the Referer Information

To limit what Referer data is available in requests from your website, you can set a "referrer policy." There are eight different policies to choose from, each affecting what's included in the Referer header:

- No Data: No Referer header is sent.

- Only the Origin: Only the domain of the referring page is sent.

- The Full URL: The full URL, including the domain, path, and query string, is sent.

These policies can behave differently based on whether the request is from the same origin or a different one, and whether the request is secure (HTTPS) or not.

Case Study:

It's 2018, and I was riding the wave of bug bounty hunting. You know, that feeling when you're on the hunt for vulnerabilities, following in the footsteps of big incidents like CloudBleed. Little did I know that my journey would lead me to uncover what I call the "Unsubscribe Tragedy."

So, why am I sharing this now? Well, back then, I didn't have permission to spill the beans, but now that this issue still lurks in the wild, it's time to talk about it.

The story begins with an avalanche of emails from a particular company's newsletter. Fed up with the constant stream, I decided to hit that "Unsubscribe" button. But something didn't sit right with me when I landed on the unsubscribe page:

- Sensitive Info Spotted: There, right in front of me, was not just my email but also my address and phone number. Privacy alarm bells started ringing.

- The Unsubscribe Token: I couldn't help but notice that the "unsubscribe token" wasn't just about unsubscribing it was like a tracking token that followed me around the website. Every click and it was there, following me like a shadow.

Days later, I was digging into the CloudBleed issue, and a lightbulb moment struck me. If this token was everywhere, it might be leaking somewhere. That's when the real investigation began.

I decided to blow the whistle and report the issue to the company responsible for the marketing software used in the unsubscribe process. My report? It highlighted how this token was leaking to social media sites when I clicked on links to the company's Twitter and Facebook pages.

As I dug deeper, I discovered that the company behind the marketing software was no small fry. They were a major player in the marketing software industry, on the cusp of being acquired by Adobe. This gave me all the motivation I needed to keep going.

I initially set out to find ways to exploit this token on a large scale. But then, a thought struck me: if it's attached to every URL a user visits, it's got to be archived or cached somewhere.

Naturally, I turned to search engines. Google showed me over 50,000 results related to these tokens. But it was Bing that blew me away. It spat out over 500,000 results. I suspected Google was playing it safe due to regional restrictions.

With evidence in hand, I reached out to the company's Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) through LinkedIn. To my surprise, they responded warmly and we had several fruitful discussions. The company agreed to address the issue, even though they didn't run a bug bounty program. They also decided to reward me for my discovery.

But the story doesn't end there. The company implemented a new configuration allowing users to prevent token leakage. This opened up another avenue for me to spot misconfigured instances and report them, contributing even more to my earnings.

In the end, the "Unsubscribe Tragedy" taught me the importance of staying vigilant in the realm of cybersecurity. It showed how a seemingly harmless feature, like an "unsubscribe" button, can become a major security threat if not handled correctly.

And for those curious about how data could have been leaked, here are some examples:

- User Profile Leaked: Imagine a link like

https://example.com/profile?user=12345. Clicking on this could expose the user's profile information, including their user ID. - Cross-Origin Data Leak: Take

https://example.com/sensitive-data. External resources linked on this page could unintentionally reveal sensitive data to other domains which led to the leakage to the search engines.

These examples show how mishandling the "unsubscribe" token and Referer headers can lead to data leakage and security vulnerabilities.